Teaching Reading in Tanzania

Language background

The language landscape in Tanzania is quite complicated. There are roughly 120 different “tribes” each with their own mother tongue, and those tribal languages are for the most part not mutually intelligible. After Tanzania gained independence in 1961, the first president, Julius Nyerere, established Kiswahili as the national language in an effort to unify the country. Kiswahili was the language used for trade, especially along the east coast of the country, and was not the mother tongue for any particular tribe.

Language in schools

All instruction in Tanzanian public primary schools is now in Kiswahili. All instruction beyond primary school, i.e. beyond grade seven, is in English. In primary schools English is taught as a lesson beginning in grade three, but the level of instruction is quite basic. The teachers themselves are often not very strong in English, a problem exacerbated by the exam-centric nature of the schooling system. Students who do well in their “Ordinary Level” exam (after four years of secondary school) are eligible for Advanced Level high school studies, and from there they can go to university. Students who don’t do as well on their Ordinary Level exams are still eligible to go to diploma programs at a teacher’s college, which is generally preparation for teaching primary school. Since Ordinary Level studies and exams are all in English, students who didn’t do well in those exams are often those who struggle with English. And they are the ones going on to teach primary school, so the difficulties with English are perpetuated.

Many Tanzanians with means have seen the problem with an educational system that switches the language of instruction mid-way through a student’s career. There are now many private primary schools, especially near urban areas, that teach using English as the medium of instruction. Of course, these schools (but not Twegashe!) charge high fees, so for the most part they are not accessible to many children.

Teaching reading in Kiswahili

Although some of Twegashe’s teachers hold university degrees, and all of them are strong in English relative the average teacher in nearby public schools, we still see difficulties with English, especially in pronunciation. These difficulties create challenges when they are teaching children to read in English. These challenges become even more understandable after looking at how reading is taught in Kiswahili.

Kiswahili developed as a trade language, and consequently is relatively simple in construction and pronunciation. There are five vowel sounds corresponding to the five written letters a, e, i, o, u:

Kiswahili developed as a trade language, and consequently is relatively simple in construction and pronunciation. There are five vowel sounds corresponding to the five written letters a, e, i, o, u:

- a [æ] or “ah” as in the British pronunciation of “cat”

- e [ɛ] or “eh” as in the American pronunciation of “bed”

- i [iː] or “long e” as in the American pronunciation of “see”

- o [oʊ] or “long o” as in the American pronunciation of “go”

- u [uː] or “long u” as in the American pronunciation of “food”

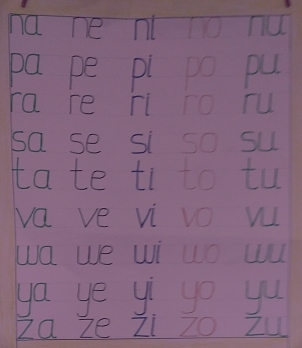

Reading is taught by drilling children on the “syllable” combinations of a consonant plus each of these five vowel sounds. You can often hear chants of “ba, be, bi, bo, bu; da, de, di, do, du; ta, te, ti, to, tu; etc.” coming from primary school windows. Add a few consonant combinations, for example, “cha, che, chi, cho, chu”, add the rule that the accent is always on the second last syllable, and “Presto!”, you can read in Kiswahili!

Practice

Try it yourself. Read the phrase below aloud, then compare to the recording.

Practice phrase: “Jana tulikula samaki.”

Check yourself: Here’s a link to a recording of a Tanzanian reading the same phrase.

How did you do? Of course, you may not know what it means, but you were probably able to “read” the words phonetically. (Incidentally, the phrase means “Yesterday we ate fish”, which is a safe bet in Bushasha Village, right on the shore of Lake Victoria!)

This is how our Tanzanian teachers learned to read, and this is how they learned to teach reading. We were astonished when one of our teachers mentioned that prior to being at Twegashe she had never been exposed to sounding out words letter by letter, as in “c – a – t” becomes “cat”. And she has a university degree in K-12 education and had been teaching at a private English-medium primary school for several years.

Challenges

It’s not surprising that our teachers, even after being exposed to sounding out words by letter, are challenged when tasked with teaching kids to read in English, with its myriad vowel sounds and its many rules and exceptions to the rule. The local language in the Bushasha area, Kihaya, has the same five vowel sounds as Kiswahili since it is also a Bantu language. Most of our teachers are Wahaya, and have a limited repertoire of vowel sounds. Recognizing, let alone making, some of the vowel sounds in English is difficult for them. Hearing the difference between the “L” and “R” sounds is another difficulty, especially for native Kihaya speakers. At the teachers’ request, we often insert brief pronunciation practices into our staff meetings to help them with these issues.

One particularly difficult vowel sound is the short “o” sound, as in the American pronunciation of “hot”, which doesn’t exist either in Kiswhaili or Kihaya. Another is the short “i” sound, as in “fish”, which is also absent in these two languages. On top of that, the name for “e” in English is the same as the pronunciation of “i” in Kiswahili. Students have trouble differentiating “names” and “sounds” of letters: They haven’t been learning their ABC’s since they were two years old, and some of them attended a year of kindergarten in Kiswahili at the local public school before coming to Twegashe, where they learned the Kiswahili sounds of the letters. So to tell them that the name of the letter “e” is what they know from Kiswahili as the sound of “i”, and that the sound of the letter “i” is a sound they’ve never even heard before, becomes extremely confusing. Now imagine you are the teacher, not comfortable yourself with the short “i” and “o” sounds, teaching your students, for example, the “silent e” rule that if you put an “e” on the end of “bit” the “i” says its name to become “bite”. It’s a perfect recipe for confusion! And as if this weren’t enough, there is the huge added handicap of children having a very limited English vocabulary.

Read Well curriculum donation

All of this is to say that we are extremely grateful to our board member, Steven Burdick, a retired teacher who saw the importance of a structured reading curriculum for Twegashe’s students. Steven has donated the materials for a curriculum called “Read Well” that we are piloting now with our first graders. So far, the feedback from students and teachers alike is very positive. The beauty of this curriculum is that it starts from the very beginning, and is even adaptable for students with limited English. Twegashe students love books, and many of our second-graders are already able to read basic readers, despite all the handicaps they face. Armed with instruction using this new curriculum, these children will be able to travel very far in their reading adventures!

All of this is to say that we are extremely grateful to our board member, Steven Burdick, a retired teacher who saw the importance of a structured reading curriculum for Twegashe’s students. Steven has donated the materials for a curriculum called “Read Well” that we are piloting now with our first graders. So far, the feedback from students and teachers alike is very positive. The beauty of this curriculum is that it starts from the very beginning, and is even adaptable for students with limited English. Twegashe students love books, and many of our second-graders are already able to read basic readers, despite all the handicaps they face. Armed with instruction using this new curriculum, these children will be able to travel very far in their reading adventures!